The Goldilocks Kōan: Why there are no “just right” names for AI

By Lindsey DeWitt Prat, PhD

January 25, 2026

The debate over the right words for AI is longstanding, with a fresh round playing out right now. What’s missing, as always, are global perspectives. I followed “hallucination” and its alternatives into Kiswahili and Japanese. In East Africa, a divergence between hitilafu (glitch) and uzushi (fabrication) asks whether we are dealing with a broken tool or an untrustworthy narrator. In Japan, the search unearths 17th-century ghost stories and the Buddhist concept of māyā (illusion). These linguistic forks suggest that perfect names don’t exist, because “just right” was an illusion all along.

Photo by the author. Baekdamsa Temple in Seoraksan, South Korea, where I did meditation retreats after years of Buddhist textual study for my PhD. Sometimes you gotta sit with a lot of words and names to finally start breaking through them.

You reach for the name that’s just right.

The name reaches for you.

What do your hands hold?

A kōan is more than a riddle with a clever answer. It’s a question designed to short-circuit habitual thinking, to stop the grasping mind in its tracks.

We could use one right now, because there’s been a fresh round of discussion by big names—and names that frankly should be much bigger—about names and AI. The terms in question: intelligence, assistant, hallucination, tool, reasoning, understanding. Oh, and “AI” itself, hence the kōan.

The search for the right names is led by a superstar. Mustafa Suleyman, CEO of Microsoft AI, argues that we are trying to describe the future with metaphors of the past. He says terms like “assistant” fail because no assistant can “run 100 billion operations per second,” while “tool” fails because it suggests a passivity that ignores the system’s “emotional intelligence.” Suleyman calls for “new Goldilocks terms” that are “just right,” accurate without overselling the machine’s humanity or underselling its capabilities.

On “tool,” some careful thinkers surprisingly agree—though for opposite reasons. Suleyman rejects it because it undersells the system’s power. Nataliia Laba and Pontus Wärnestål reject it because it obscures the system’s power over users. A tool is an object you control; a service is something that controls you, politely, via terms of use. Calling AI a “tool,” they argue, maintains the illusion of user control while offloading accountability onto the public.

Others argue the problem isn’t the metaphor, but the lack of precision. Scholars like Emily Bender and Nanna Inie, and Timnit Gebru warn that terms like “learning” or “hallucinating” are “wishful mnemonics,” labels that trick us into seeing a mind where there is only math. They push for functional descriptions of what the system does rather than what it “knows.” Michael Hicks and colleagues went further and argued back in 2024 that we should abandon “hallucination” entirely for “bullshit,” noting that these systems are structurally indifferent to the truth.

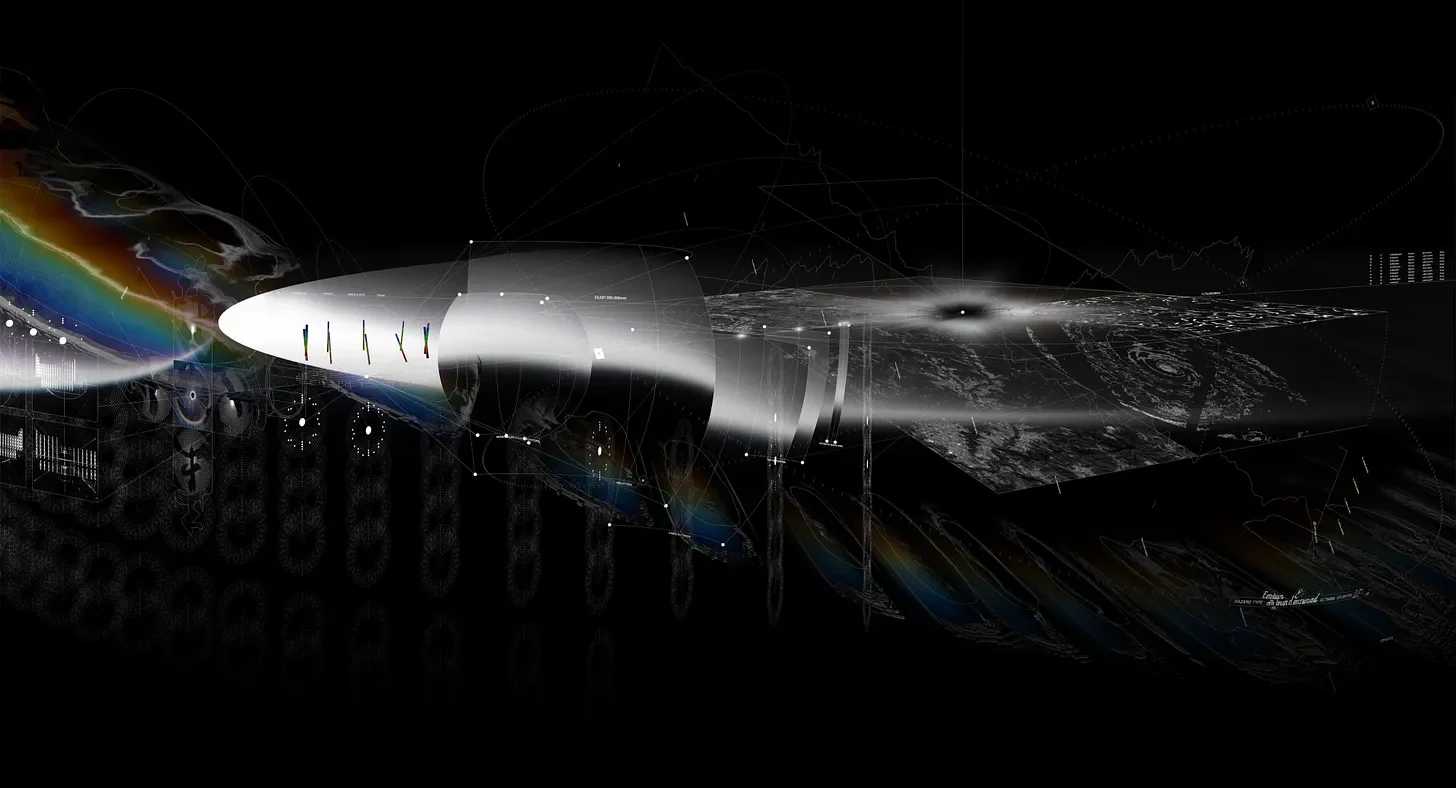

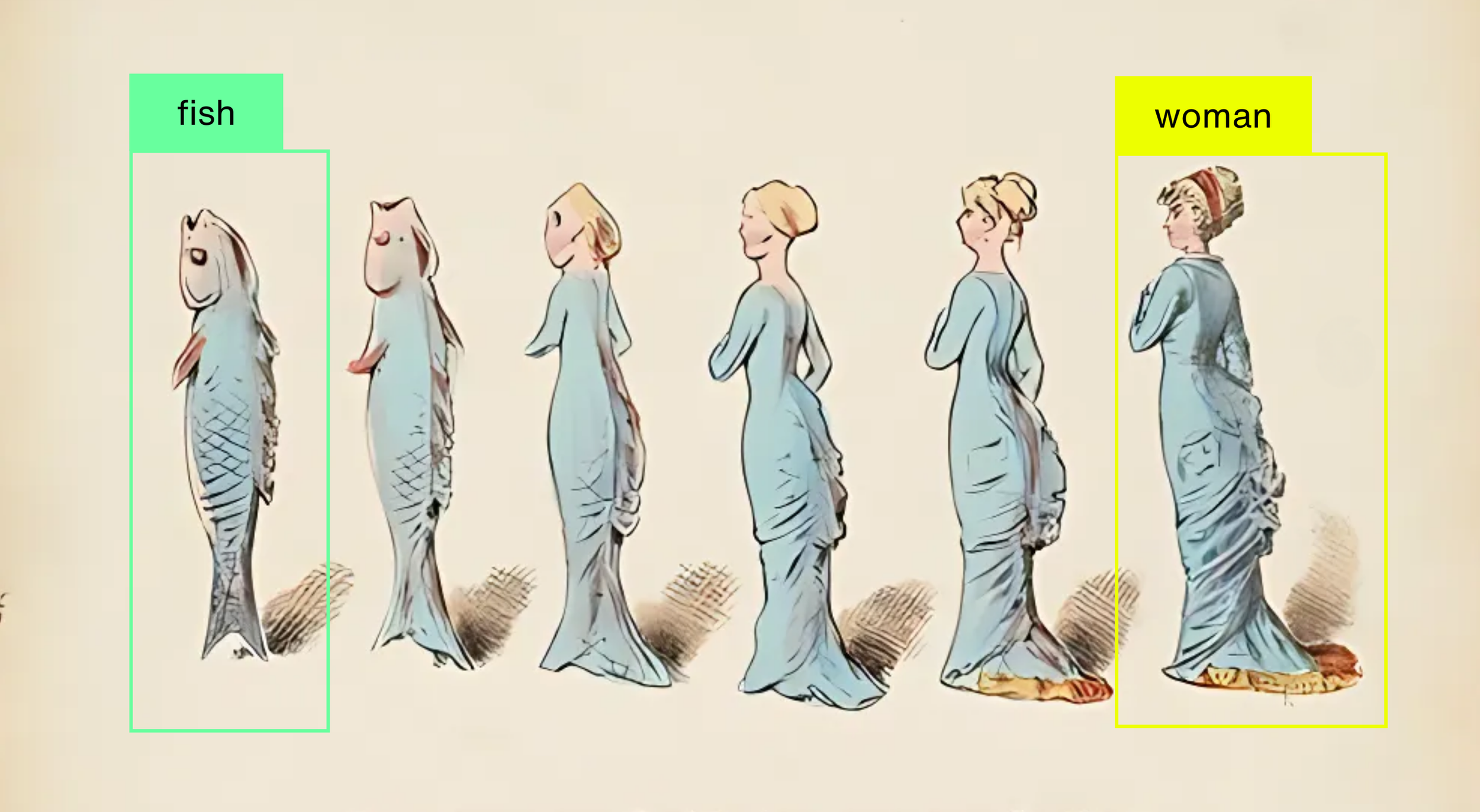

Finally, some say our vocabulary—visual and verbal—is simply impoverished. Strategist and prolific thinker Zoe Scaman suggests we look to biology and software for terms that encode honest power dynamics: fork (to reclaim agency), daemon (to name the background intimacy), and symbiont (to acknowledge dependency), among others. Absolutely brilliant design projects have been attacking the visual front. Better Images of AI curates a library replacing glowing brains and blue robots with honest depictions of hardware and labor. Archival Images of AI contributes pieces like Nadia Piet’s “Limits of Classification”—a fish morphing into a woman, where neither label holds. Metaphors of AI adds narrative frames back in, as in “AI is a Game of Words” (below), which depicts it as a deck of cultural cards shuffled differently depending on who holds them.

Different positions, different strategies, but there’s a shared insight: names and frames have power. They determine what questions we ask and who gets to answer them.

Here’s where I’ve been digging: one word, many forks, to borrow Scaman’s metaphor. The word is “hallucination.” And the driving question is: what happens when we open the aperture of the naming discussion and go global with it?

Pre-Fork: Inherited Frames

The term “hallucination” entered discourse around computing decades before ChatGPT. Here’s a basic sketch—I highly recommend Joshua Pearson’s 2024 history of the term for a richer take on the foundational genealogy.

In 1982, computer scientist John Irving Tait, studying at the University of Cambridge, used it to describe a text-parsing system that “sees in the incoming text a text which fits its expectations, regardless of what the input text actually says.” The system hallucinated matches, meaning it misapprehended.

That framing won out over an alternative. In image processing, US-based researchers in the 1980s and ‘90s used hallucination differently, to describe generative capability. Eric Mjolsness’s 1986 Caltech thesis discussed neural networks “hallucinating” fingerprint patterns from random input. For Mjolsness, the ability to produce coherent structure from noise was the feature, not the bug. But the generative usage stayed local to computer vision, never crossing into chatbot discourse (Maleki et al., 2024).

What traveled was the text-processing frame: hallucination as the bug, as a deviation from an otherwise truthful system. The word traces to Latin roots meaning either “to mislead” or “toward light”—sources disagree. Although “hallucination” appeared in English as early as the seventeenth century, it was nineteenth-century psychiatry that cemented the frame we inherited, as a specific pathology, a deviation from sanity requiring correction.

The pathological frame is what crossed into other languages. The question is what it encountered when it arrived. Wikipedia hosts 83 in-language pages for “hallucination,” 31 for hallucination in the context of artificial intelligence, and no two are the same. Profound technical, cultural, and methodological differences separate the entries: the Russian page frames the error as a “sociopathic” driver of disinformation, the Chinese page dissects it as a failure of logical taxonomy, Spanish editors pivot immediately to corporate liability.

83 forks are too many to trace here, as are 31, but how about two? Kiswahili, where rival glossaries are taking shape as we speak; and Japanese, where the etymological trail leads to strange—even ghostly—terrains.

Fork: Kiswahili

A quick note: I’m not a Kiswahili speaker or an African languages and cultures specialist. I’ve drawn on publicly available sources here and am reporting what I’ve found.

In East Africa, the effort to localize the tendency of a computational system fabricating information arrived at different terms rather than consensus, even when many of the same institutions and experts were involved. The divergence didn’t stem from disagreement about whether AI literacy matters but from different answers to a prior question: what kind of understanding should the name invoke?

One lineage begins with a story. In 2022, UNESCO published Inside AI, a graphic novel designed to explain algorithmic systems to general audiences through narrative and illustration. The book walks readers through how AI systems are trained, where they fail, and why those failures matter, using everyday scenarios. In 2023, the UNESCO Regional Office for Eastern Africa produced its Kiswahili translation, Ndani ya AI, describing it as “one of UNESCO’s first experimental efforts to express and communicate complex technical terms in simple language” (UNESCO 2025). The core aim was pedagogical clarity: helping readers recognize error, limitation, and misalignment without requiring prior technical expertise. Notably, this version avoids “hallucination” altogether. Where the English edition uses “glitch,” the Kiswahili uses hitilafu, a term for malfunction or error. The framing is mechanical: something went wrong with the system.

Panels from UNESCO’s Inside AI - An Algorithmic Adventure using “glitch” where hallucination might be deployed.

Panels from UNESCO’s Ndani ya AI: Ziara ya Algorithi using “hitilafu” where a translation for hallucination might be deployed.

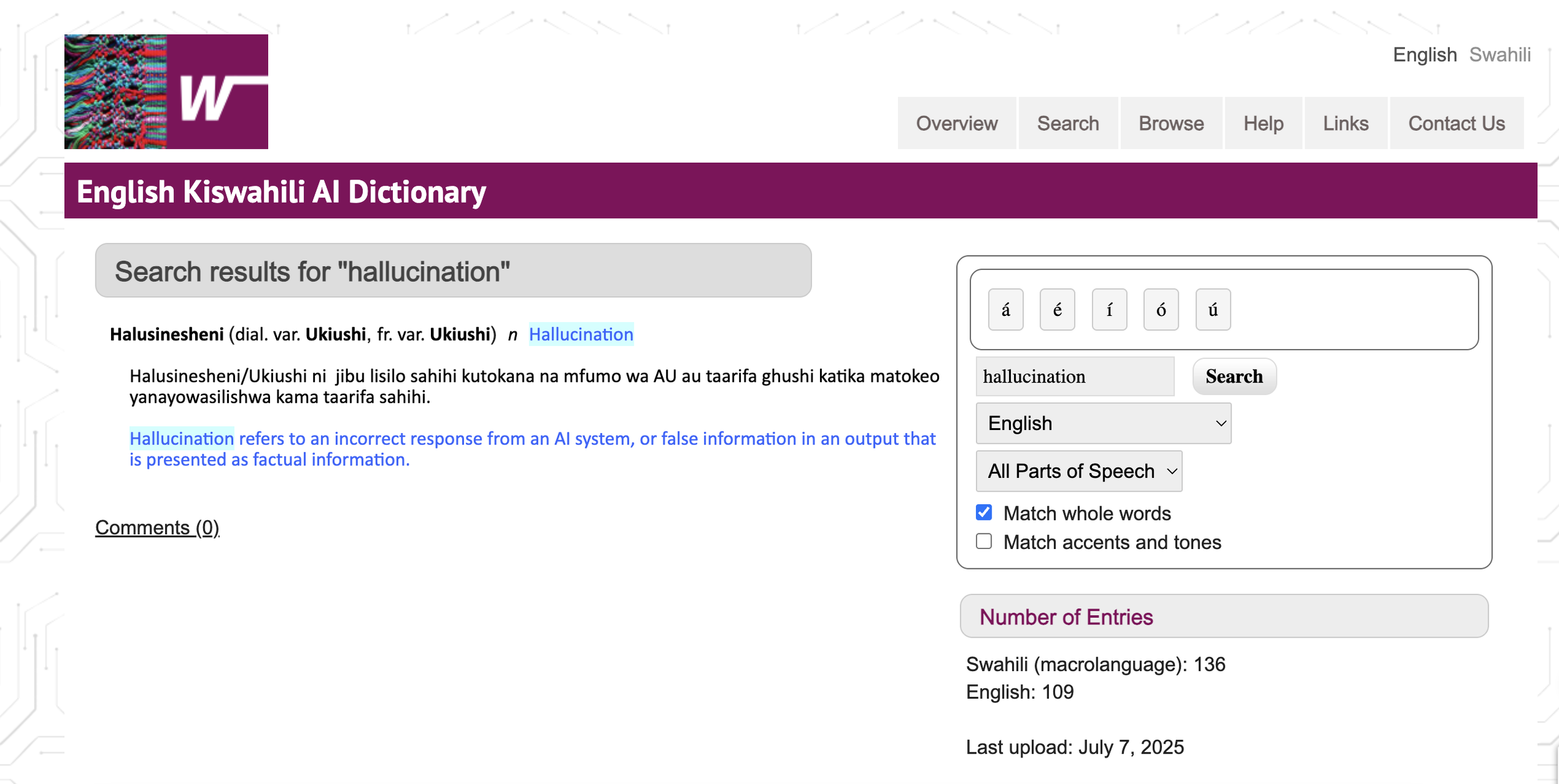

That pedagogical approach carried forward into the 2025 English–Kiswahili AI Dictionary (below, first image), though with a shift. Also produced by the UNESCO Regional Office for Eastern Africa, the dictionary extended the logic of the graphic novel into a reference form. But where the graphic novel sidestepped “hallucination,” the dictionary addressed it directly, prioritizing the loanword halusinesheni and listing ukiushi (transgression or deviation) as a dialectal variant. The definition frames the phenomenon as functional error: jibu lisilo sahihi (incorrect answer) or taarifa ghushi (fake information). The emphasis is on accuracy, deviation, and correction. The system produces something it should not have, and the task is to recognize and fix that failure.

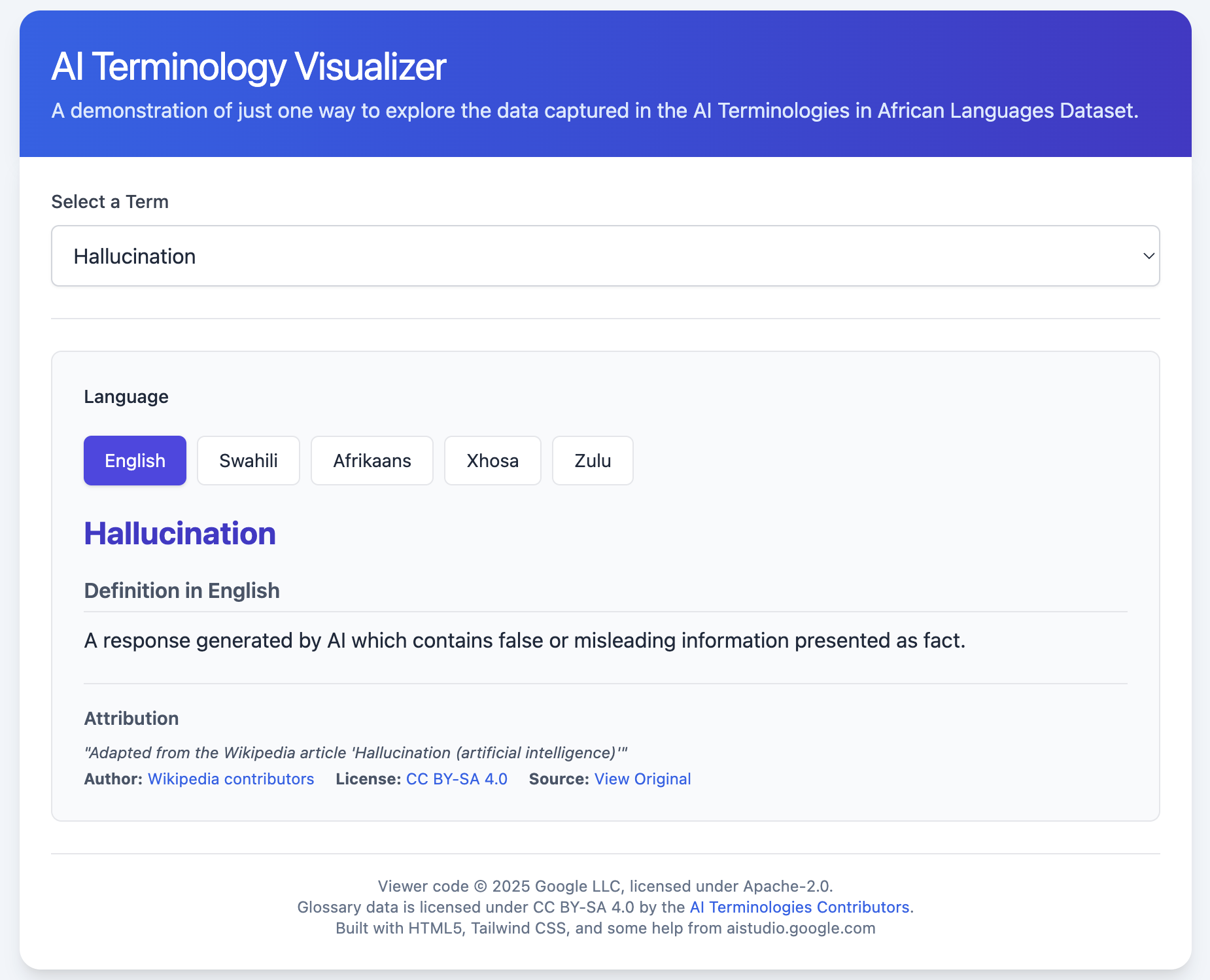

A parallel effort took a different approach. Google’s 2025 AI Glossary for African languages (below, second image) emerged from a separate initiative involving workshops and round-table discussions across four East African languages (Swahili, Zulu, Afrikaans, Xhosa). The process brought together national language bodies such as the National Kiswahili Council (BAKITA), lexicographers, AI experts, and representatives from UNESCO. The stated goal was broad user understanding and engagement, explicitly tied to bridging the digital divide and encouraging everyday uptake of AI-related language.

For “hallucination,” the glossary lists uzushi. From here the trail gets really interesting, perplexing even. The attribution points to Wikipedia’s English-language page for “hallucination (artificial intelligence).” But that page has no Swahili parallel. The Swahili Wikipedia page for uzushi, on the other hand, makes no mention of technology. Instead, it links to the English page for “rumor” and defines uzushi as spreading false information with intent to humiliate or damage reputation. A Swahili speaker encountering uzushi in Google’s AI glossary and then searching Wikipedia would find not artificial intelligence, but the social dynamics of gossip.

Screenshot from the English Kiswahili AI Dictionary showing hallucination rendered with the transliteration halusinesheni.

Screenshot from Google’s AI Terminology Visualizer showing hallucination translated into Kiswahili as “uzushi” and attributed to an English Wikipedia page for “Hallucination (artificial intelligence).”

Across multiple Swahili lexical sources, the term traces to the root -zusha, commonly glossed as to invent, fabricate, or stir up trouble (e.g., LughaYangu, MobiTUKI [based on work by the Institute of Kiswahili Research at the University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania]). A 1967 Swahili–English dictionary in the UNESCO library lists uzushi among senses that include “rumor” or “gossip,” illustrated with an example glossed as “pure fabrication” (p. 609). On translation sites such as Glosbe, uzushi is most often rendered as “rumor,” but also associated with religious notions of “heresy” and, in at least one source, with “witchcraft.”

For an academic perspective, Dr. Cristina Nicolini’s 2022 study of HIV/AIDS discourse in Swahili literary genres gives uzushi a weight far heavier than mere incorrectness. In her analysis of a work by Tanzanian intellectual William Mkufya, uzushi names the heresy of religious myths, specifically fabrications that distort the reality of life and death and damage communal well-being (p. 294).

Let’s take stock.

The UNESCO graphic novel’s hitilafu frames the problem as mechanical failure; the UNESCO dictionary’s halusinesheni, a direct loanword, tracks back to the English frame of faulty perception. One diagnoses a broken tool; the other imports the pathology. Google’s uzushi does something different: it identifies an untrustworthy narrator. None is “wrong,” yet is any sufficient? That’s an open question. But the gaps between them matter. To use hitilafu is to locate the problem in machinery. To use halusinesheni is to locate it in perception. To use uzushi is to locate it in character and intent. The name determines what is accountable: a broken system, a misfiring mind, or a dubious agent.

Fork: Japanese

Now onto more familiar territory in East Asia. When Japanese publications discuss hallucination in the context of AI, they typically write it two ways: ハルシネーション/幻覚 (harushinēshon/genkaku). Japanese uses multiple writing systems. The angular script on the left, katakana, is reserved for foreign loanwords. Here the English “hallucination” is simply sounded out phonetically. The dense characters on the right, kanji, are inherited from Chinese and carry meaning: 幻 (illusion, phantom) + 覚 (perception, awakening). One imports a sound; the other offers a gloss. The gloss brings its own baggage—or better, invites us to pack our bags for a journey.

First up is the the authoritative Brain Science Dictionary (脳科学辞典, Nō Kagaku Jiten), neuroscientist Fukuda Masato defines hallucination (幻覚, genkaku) as perception without an object (対象なき知覚, taishō naki chikaku) and categorizes it primarily as a symptom of schizophrenia (統合失調症, tōgō shitchō shō), dementia, or drug toxicity (Fukuda 2021). This framing tracks with the dominant English one: in which hallucination signals dysfunction, a symptom to be treated.

Linguistic and aesthetic scholarship treads down a different path. Shōichi Yokoyama (横山詔一), Professor Emeritus at the National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics (NINJAL), argues that we cannot have the “sunlight” (陽光, yōkō) of generative creativity with the “shadow” (影, kage) of hallucination (Yokoyama 2025, p. 9). He reframes these errors not as bugs but as “white daydreams” (白昼夢, hakuchūmu), machine outputs that mirror the chaos of human dreaming (p. 8).

This language risks the anthropomorphic trap criticized by scholars like Bender—projecting interiority where there is only statistical prediction. But Yokoyama’s argument is not that the machine dreams. It is that the output, read through poetic context and aesthetic framework, opens space for human interpretation. He draws on classical Japanese sensibilities: yūgen (幽玄, mystery and depth), aware (あはれ, pathos), the Heian literary tradition, and Zen Buddhism, which of course gave us the kōan. Through these lenses, factual error transforms into expressive possibility (表現の可能性, hyōgen no kanōsei).

Yokoyama calls this process artistic participation (芸術的参与, geijutsuteki sanyo): a creative act of reading where value is reconstructed through context and the receiver’s sensibility (受け手の感性, ukete no kansei) (pp. 5, 11–12, 16). The hallucination becomes an opening for co-creation regardless of its factual wrongness. Instead of asking only what the system is doing, Yokoyama wants us to consider what the perceiver is doing with what they hold. This reading moves us closer to the heart of our Goldilocks kōan: instead of asking only what the system is doing, Yokoyama asks what the perceiver is doing with what they hold.

Digging deeper still, the vocabulary of computational error opens onto much older trails. Follow “confabulation” and you might land in the floating world of early modern Osaka. Follow “hallucination” and step into Buddhist philosophy. Neither path is obligatory, but both open onto ways of thinking that might actually help us meet this moment in all its complexity. The dominant English frame makes no space for them.

A literary trail

The Japanese clinical term for confabulation (作話, sakuwa) uses characters that can also be read tsukuribanashi, a native Japanese reading that shifts the semantic field from clinical diagnosis to storytelling. It basically means an exchange 話 that is constructed 作, from which we can interpret something made to seem true when it is not, something spun from imagination rather than fact.

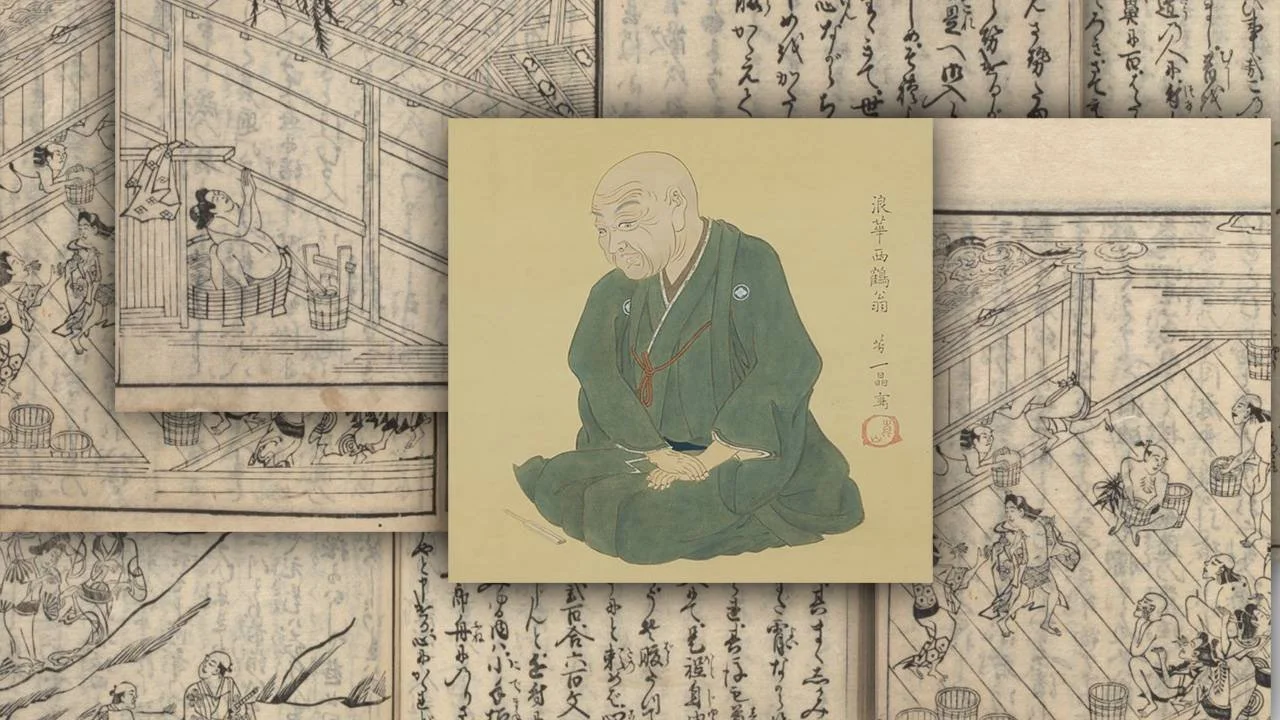

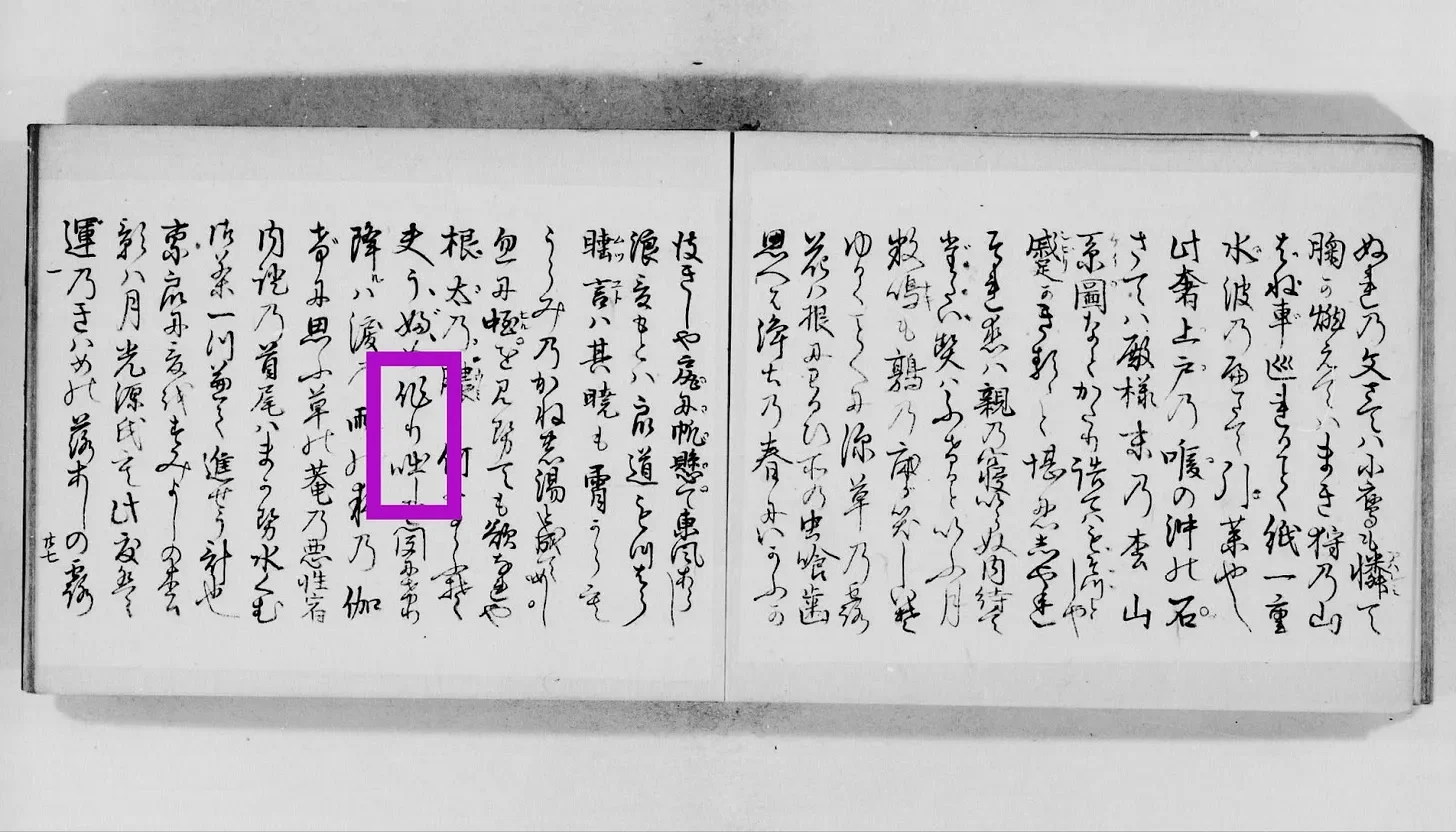

The earliest recorded usage appears in a 1681 text by Ihara Saikaku (井原西鶴, 1642–1693) called Saikaku Ōyakazu 西鶴大矢数 (Saikaku’s Great Number of Arrows). More on the text in a moment, first a little about the author.

Image collage from https://mag.japaaan.com/archives/170082; Saikaku portrait from Wikipedia.

If early modern Japan has a figure comparable to Defoe or Cervantes who helped invent prose fiction as a popular commercial form, it’s Saikaku. He began as a poet in the haikai 俳諧 tradition, a collaborative game in which participants improvise linked verses in rapid succession, riffing on each other’s images and wordplay. It was social, competitive, and valued spontaneity over polish. Then woodblock printing created something new: a mass reading public hungry for stories. Saikaku pivoted to prose fiction and became the first major writer to feed that appetite.

The floating world (浮世, ukiyo) was Saikaku’s milieu (as Thomas Gaubatz’s recent book explores), referring to the urban pleasure quarters of Osaka and Edo, where newly rich merchants spent lavishly on geisha, kabuki theatre, and sensual pursuits. The term itself is a pun: it sounds identical to the Buddhist sorrowful world (憂き世, ukiyo), the realm of suffering and impermanence, but the character for “sorrow” 憂 is swapped for “floating” 浮. Pleasure layered over transience; the pursuit of fleeting beauty as a way to survive the fact that nothing lasts—or at least make it seem stylish.

The text Saikaku Ōyakazu (pictured below) was born out of a marathon session in which Saikaku composed 4000 verses in a single day and night, flow and wit mattering far more than fidelity to fact. In one passage, Saikaku describes hearing the—wait for it—tsukuribanashi of an ubume (産女), the ghost of a woman who died in childbirth yet lingered to care for the living. The text calls her story “a night’s entertainment” amidst “falling tears.”

A page from Saikaku Ōyakazu (1681), University of Tokyo Library. The earliest recorded use of tsukuribanashi (characters also read sakuwa, the modern clinical term for confabulation, a cousin of hallucination).

Let’s take stock.

Tsukuribanashi is the storytelling face of confabulation, itself a cousin of hallucination. It first appears in the mouth of a ghost, in a text born of marathon improvisation, for an audience experiencing thrashy times in an urban hubbub. Layers of agency fold into one another: Saikaku invents the ghost who tells a story made to seem true, and we receive it as entertainment. In this context, “perceptual error” has no purchase. This is a name for fabrication as gift, not defect.

Three centuries later, we scroll through outputs generated at speeds Saikaku could not have imagined, from systems that produce compelling resemblances indifferent to truth. We are, again, in a floating world and spitting out words to capture the experience.

A philosophical trail

This path runs separately, through Buddhist lexicography. The trail stretches back at least two millennia and across at least two continents.

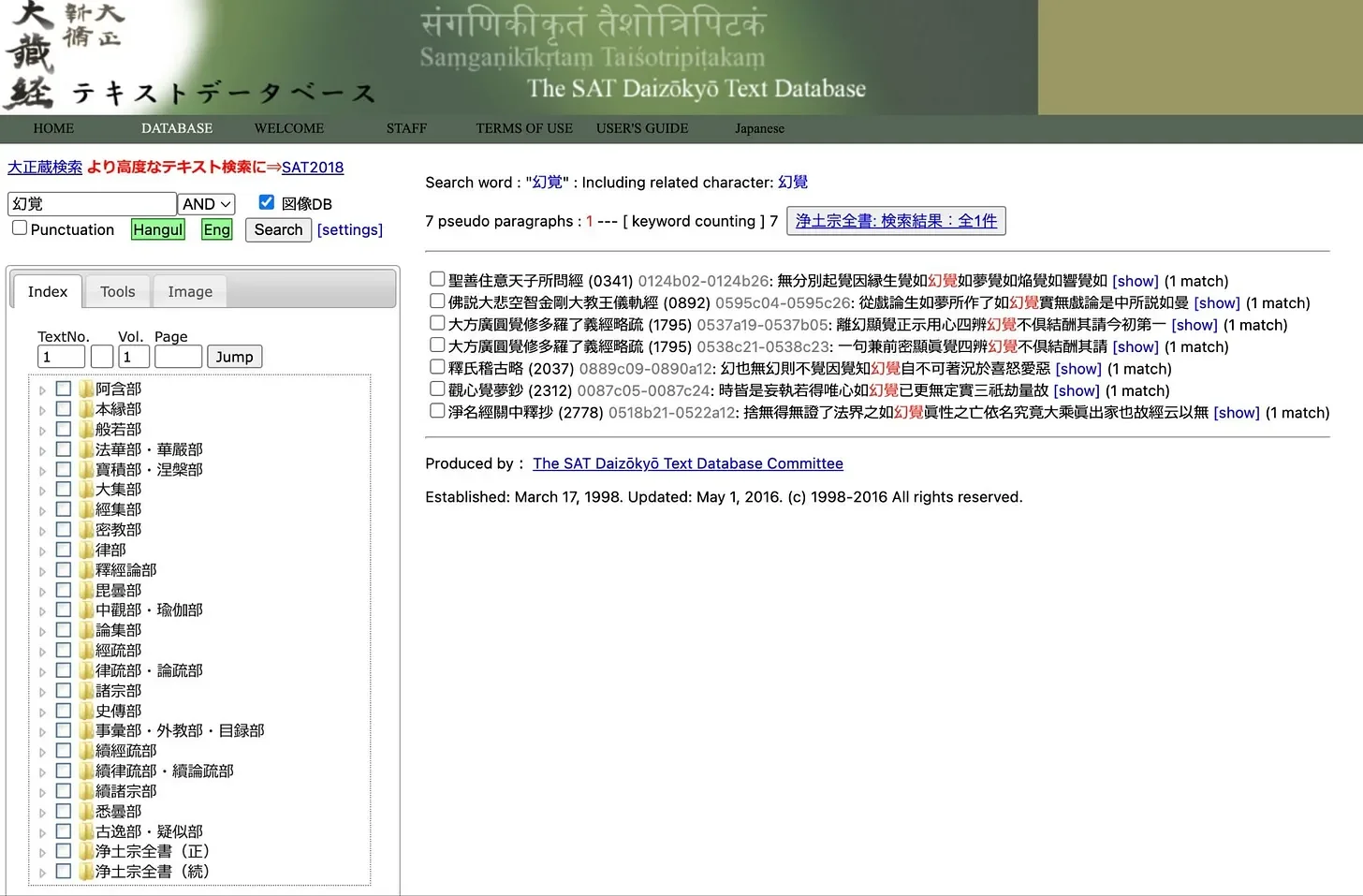

A decade ago, this would have been a research trip. I spent years in the stacks at UW and UCLA, handling manuscript editions of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean (CJK as we called it) Buddhist texts. Very few things were digitized but we had custom CD-ROMs with hand-scanned resources and early database prototypes like the fantastic Digital Dictionary of Buddhism. Now I can sweep the entire SAT Daizōkyō Text Database (a digitized version of the Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō, the authoritative modern edition of the Chinese Buddhist canon compiled in Japan between 1924 and 1934) in seconds.

Screenshot of search results for 幻覚 (genkaku, a common gloss for “hallucination” in Japanese) in the SAT Daizōkyō Text Database.

So that’s what I did. Searching for 幻覚, I found seven occurrences across the canon’s roughly 2,500 texts, scattered across sutras, commentaries, and esoteric ritual manuals. This needle in the haystack is exactly what digital search was made for.

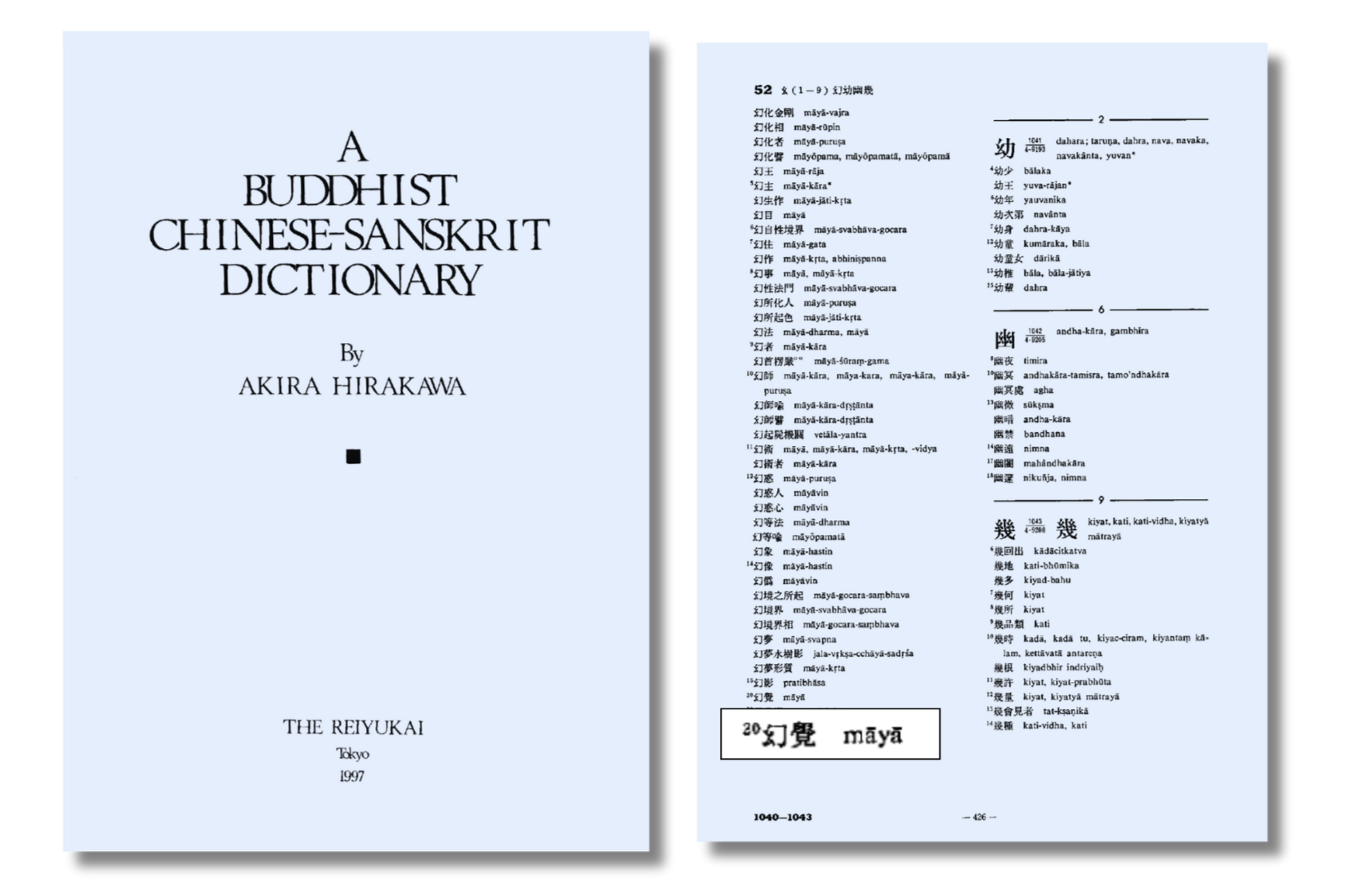

The trail led next to the Digital Dictionary of Buddhism. No entry for 幻覚, but a referral: “You may wish to consult the following external source(s): Buddhist Chinese-Sanskrit Dictionary (Hirakawa) 0426.” Curiouser still, I did, and there was genkaku, mapped to māyā.

A word about the Hirakawa Buddhist Chinese-Sanskrit Dictionary. When Buddhist texts traveled from India to China along the Silk Road—roughly the second through tenth centuries—translators rendered Sanskrit concepts into Chinese characters. Hirakawa Akira’s dictionary, published in 1997, represents decades of scholarly labor to reverse-engineer those translations: to trace the Chinese terms back to their Sanskrit originals, with English translations that open the archive to scholars and curious readers beyond East Asia. The dictionary is a map of a map, logging correspondences across two millennia, multiple languages, and thousands of miles. Pulling on 幻覚 and finding māyā, we are following a thread that stretches from modern Tokyo back through medieval China to ancient India to the device in front of you.

In Buddhist philosophy, māyā refers to the nature of the phenomenal world itself: things appear real, coherent, vivid, yet lack inherent essence. Far from a defect in perception, māyā is the condition under which perception occurs. The world presents itself as solid, and we buy into it. That solidity is the illusion.

The payoff of the tracing—some outlier data if I’ve ever encountered it—is that māyā reframes the hallucination question entirely. The term points to a basic human predicament: we crave certainty, stability, solid ground, and we suffer when the world refuses to provide it. Our names project that craving. We say “hallucination” and assume a stable truth of technology against which errors can be known or measured. We imagine language can pin the thing down.

Through the lens of māyā, the pinning is the problem. Appearances arise. They feel vivid, coherent, real. An interface speaks to you in natural language. An output that conveys certainty arrives with an air of magic. These are appearances doing what appearances do.

The naming debate looks a little different from this vantage. Suleyman wants Goldilocks words, terms that are “just right.” Others want linguistic precision, or richer metaphors. But no name escapes the condition it tries to name. Even “bullshit” is a word reaching for purchase on something that keeps sliding. The search for the right term may itself be the wrong search. Naming matters, but expecting to find the settled word mistakes the map for the territory.

The territory is māyā all the way down.

AI researcher Youichiro Miyake is working in this territory. Miyake contrasts a “Western AI” built on Cartesian logic and functionalism with an “Eastern AI” rooted in Buddhist ontology (Miyake 2023). The distinction, he argues, is encoded in language itself. In a recent lecture (available online in Japanese), Miyake argues that the standard Japanese term for AI, jinkō chinō (人工知能), imports a Western functionalist trap. Chinō implies “intelligence as ability,” a brain measured by what it does. He proposes jinkō chisei (人工知性) instead. Chisei implies “intelligence as being,” a presence that exists before it has any utility at all. One names a servant to be tasked. The other names a presence to be met.

What Miyake describes as Eastern AI starts with chaos (混沌, konton) and prioritizes existence over function. In his words from a 2022 interview: “They define problems in the West, but starting from chaos is the basic format for oriental philosophy. The world is inseparably interwoven with the self—this is where this philosophy begins.”

Let’s take stock.

“Western AI” asks: What is the system for?

“Eastern AI” asks: What kind of presence is this?

The māyā frame pushes further still: Are we noticing that, well, an appearance is appearing?

Miyake’s chinō/chisei distinction brings us back to where we started: the naming debate itself. “AI” encodes fundamental assumptions about what intelligence is before any conversation about hallucination or error can begin. Names like Gebru, Bender, and Inie have raised a similar concern: “AI” lumps together wildly different models, techniques, and tasks into a category that obscures more than it illuminates. Yet, forging through the forks of Kiswahili and Japanese, it’s clear that the problem runs deeper than anthropomorphism. Strip the human projections and you still face the frame. Every name carries one, and the ground is never neutral, never just right.

The Goldilocks illusion

We dove into māyā and resurfaced at the same question the essay began with: what should we call this thing, these things? Are they things? But now the question looks different. The challenge is recognizing what any name has already decided for us, put in our hands, to call back the kōan.

Remember the actual story? The porridge was tasty. The chair was her size. The bed was perfect. And Goldilocks was in a bear’s house the whole time! “Just right” was a lost child’s illusion of comfort while enveloped in danger.

This is the Goldilocks trap. We keep searching for a term that assumes there is a real bed and a real porridge that a computational system is failing to replicate. But through the lens of māyā, the search for comfort was the illusion all along. The interface that speaks fluently, the confident answer that arrives instantly: these are appearances doing what appearances do. Vivid, coherent, lacking inherent essence. The machine mirrors back our own craving for certainty. There is no “just right” to find.

Different communities will keep making different choices. Kiswahili speakers will debate uzushi versus hitilafu. Japanese discourse will carry psychiatric, literary, and philosophical traces simultaneously. English speakers will keep reaching for “hallucination” while critics propose “bullshit” or “confabulation.” None of these will settle. That’s the condition we are in.

The push for naming precision is necessary and needed: specificity beats mystification. Name what the system does, not what it “knows.” That path leads to sharper technical terms and fewer sociotechnical harms. The collaborative path leads somewhere else. Two UNESCO projects and Google’s glossary (developed with UNESCO support) aimed for shared clarity and wound up in different places. One path sharpens; another diversifies. Neither resolves the tension.

Kōan exist to bring tension front and center, and to keep the mind from drifting into comfort. So keep this Goldilocks one close as you move through 2026:

You reach for the right name. The name reaches for you. What do your hands hold?

Nadia Piet & Archival Images of AI + AIxDESIGN / https://betterimagesofai.org / https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Suggested citation: DeWitt Prat, Lindsey. “The Goldilocks Kōan: Why there are no “just right” names for AI” lindseydewittprat.com, January 25, 2026. https://www.lindseydewittprat.com/goldilocks-koan

This work is licensed under CC BY 4.0.